The Independent Recording Artist’s Guide to Infrastructure

Autonomy in the music industry is just as much about systems as it is ownership. LaRussell’s model builds for the long term in music, business and technology. These are the elements that make his music machine go.

LaRussell for AllHipHop

The music industry is still adapting to streaming. As tech innovations go, it’s a great reminder that systems are not set in stone. When downloads disrupted the CD model, it changed the way that fans listened to music. At the same time the Internet, through blogs, changed the way music could be discovered, putting more power behind voices of industry outsiders. Bloggers became authorities with platforms in their own right. Of course, changed isn’t always welcomed with open arms especially not by the old guard. At least not at first.

It was said that streaming would kill the music industry. In reality, it brings in more money than CD or digital download sales. Since 2015, the global recorded music industry has grown year over year. Change is welcomed once the revenue machine gets buzzing. The music industry is made of three parts. Part one is recorded music. Pre-streaming, music sales drove the most revenue. Second is publishing.

As the oldest vertical in the business, publishers represent composers, songwriters and lyricists to collect fees on the commercial use of their intellectual property. Today, this is where most of the revenue in the music industry comes from. The third is live music, driving revenue from concert and performance sales. While publishing is the most profitable sector, live music is the largest.

Belly, 1998

The Internet had the same impact across all media industries. Fans are no longer accustomed to paying for music, or articles or movies. Instead, content is the gateway to fandom, an entry point. Plus, there’s so much of it. With a reduced barrier to entry, aspiring artists can record and release music all from at home with the help of a Google search or two. Music labels are no longer the gatekeepers they once were, although they still have all the money.

As more recording artists choose to forgo label deals all together in favor of maintaining autonomy over their work, they must redefine their revenue models. At some point to grow one’s stardom it costs money to make and promote music. For these artists, independence is not just about ownership. It’s just as much about systems.

The pursuit of the independent recording artist is building infrastructure. West Coast rapper, LaRussell Thomas has a model that’s gaining national momentum. It’s built on pillars of music, business and technology. With music as a form of connection to his fans, LaRussell releases frequently. I count 26 projects on his Apple music page, with 7 of them from 2023. While new music comes and goes, systems are for the long term. These are the elements that make LaRussell’s music machine go.

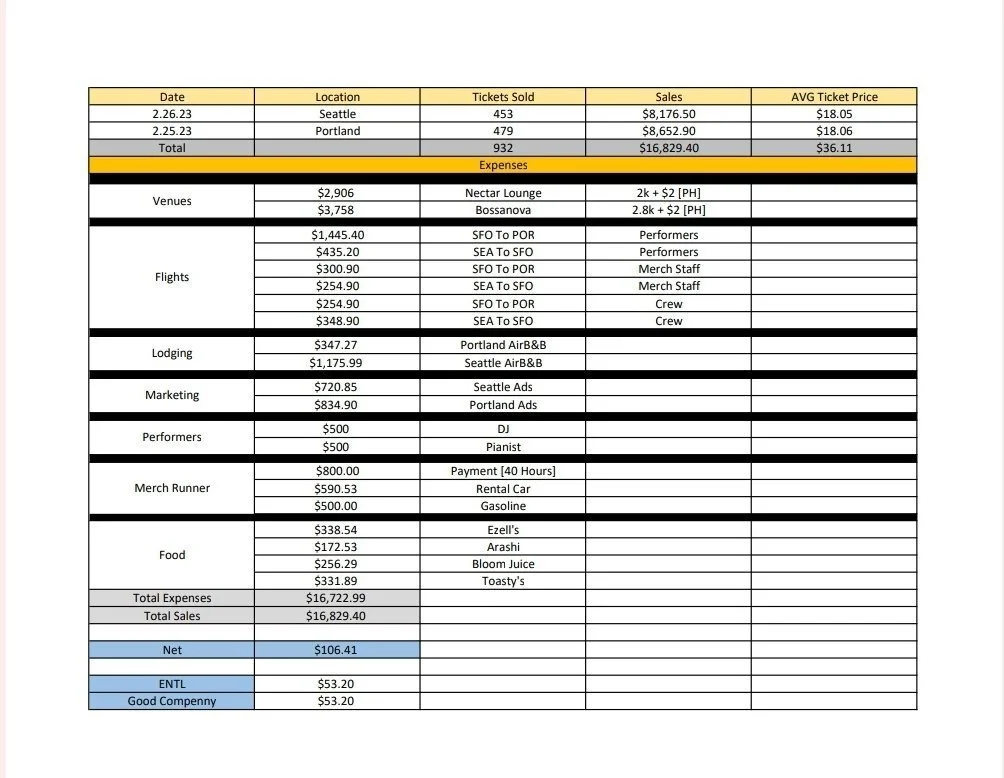

The cost of putting on a show, shared by LaRussell himself

An Intimate Fandom

LaRussell’s music thrives on the intimacy baked into his connection with fans. There’s offer-based ticketing, allowing fans of all backgrounds to experience his live performances. There’s the GC Gold Card, a lifetime membership with perks such as free access to shows, no waiting in lines and royalty splits on future releases. The crown jewel is his venue, the Pergola, home of the Backyard Residency. It came as a solution to his early concert structure, where ticketing and door deals cost more than they were worth. An artist owned venue cancels out those fees to keep the money in-house.

LaRussell calls it “the money tree” because he can announce a show and profit between $20k-$30k almost instantly. The money tree sits in his parent’s backyard. The fans are welcomed to his home. Shows take on the same nature, greeting fans as long-time friends and relying on audience participation to curate his set list. This is not your average concert.

In LaRussell’s system the guide to music is chasing fans and not streams because at a high level, monthly listeners aren’t a straightforward metric. The type of fan accumulating the streams matters. A streaming count that comes from playlist placements might mean less engaged listeners. It’s why streaming numbers don’t always correlate to ticket sales. If LaRussell can average multiple plays per listener, then those stats speak to more active consumption.

By releasing lots of music he gets them in the door. Then by treating them as an intimate part of his artistry he gets their buy-in. Compare this approach to fan building to previous eras, where mixtapes and features helped artists boost their exposure. Look to current consumer preferences to understand why fans want to feel like they are a part of a larger community.

A Label for the Greater Good

It’s easy to reduce the benefit of major labels down to their resources. They have the money, relationships and expertise to launch successful music careers. The machine. A less touted benefit, and perhaps a less offered one, is artist development. The tools to perfect one’s craft. The business of artistry. Enter the Goodcompenny Collective. It’s not quite a label, but provides the traditional benefits of one. Labels make it easier for artists to navigate their careers in exchange for money or ownership. Goodcompenny bypasses the ownership, but still stands on business.

The collective is a Bay Area non-profit with a mission to provide local creatives with resources, support and opportunities to showcase their talent and ideas. Goodcompenny doesn’t charge artists for their services.

In short, LaRussell built a model for himself and then founded a collective to show other artists how to do the same. While reimagining the path of the independent recording artist, he’s planting seeds with the potential for industry wide impact. As more artists bloom, the influence spreads.

Logistics Powered by Technology

When half the battle is the functionality to power your own concepts, sometimes you have to build your own tech. Isn’t that the story of hip-hop itself? For LaRussell, the concept of offer-based participation came first, for music, for concerts, for ownership stakes. The systems, though, were iffy. Again, the issue of infrastructure. His solution is Proud 2 Pay, the first offer-based ticketing platform. Smooth functionality to keep employing a model that works well.

Profits for offer based ticketing vary by market since venues get paid for up front. In softer markets, it’s a way to grow his fanbase. In brand strategy it’s the concept of customer lifetime value. They may have paid $2 for the first show, but if they come and have a good time, they’ll be willing to pay more at the next one.

The tech itself opens up so many options for artists. Through this offer-based model, LaRussell is able to decide how much he’s willing to accept for his work as well as curate an experience across a broad level of socioeconomic backgrounds. It all feeds back into his fandom.

To the question of infrastructure, LaRussell is a reminder to keep the possibilities open. Homegrown models become big time models with a little strategic implementation. LaRussell centers the music through his fans. He navigates the business and stamps it with the Goodcompenny Collective and he’s built the tech to power his offer-based revenue model. In the story of music, there’s growth through innovation.